Well before Black feminist, novelist, playwright, and poet Ntozake Shange ’70 gifted the Ntozake Shange Papers to the Barnard Archives and Special Collections in 2016, the College was already using her publications as teaching tools. In 2010, Kim F. Hall, Lucyle Hook Professor of English and professor of Africana studies; Monica L. Miller, professor of English and Africana studies and dean of faculty diversity and development; and the Department of Africana Studies started planning the 2013 Worlds of Shange conference and the resulting Scholar & Feminist Online issue. Using the Ntozake Shange Collection, Hall created pedagogy for the Digital Shange Project in 2014, a class often visited by Shange. Last year — with support from a Presidential Research Award — Africana studies teamed up with colleagues from the Department of Dance, Theatre, and English, and the Barnard Library and Academic Information Services, to officially launch the Shange Magic Project as a way to honor and celebrate the poet’s life and legacy. Shange passed away at the age of 70 on October 27, 2018.

“Collaborating with Ntozake and Kim, as well as engaging with Ntozake’s writings and plays, has been one of the singular joys of working at Barnard because Ntozake and Kim brilliantly bring so many people together by virtue of their artistic and intellectual capaciousness,” said Miller.

Over the years, the College has hosted many events that further the understanding of Shange’s work. As part of The Worlds of Ntozake Shange symposium in 2013, students performed excerpts from her writing set to music produced by Ebonie Smith ’07. In 2018, for the inaugural Lewis-Ezekoye Distinguished Lecture titled Diaspora and Movement, Shange sat in conversation with Sydnie Mosley ’07, lead lecturer and coordinator for Barnard’s Dance in the City Pre-College Programs, to discuss their art, movement, and the collaborations that fueled their work.

The Shange Magic Project, which celebrates sisterhood and collaboration, has produced a series of events. In October 2019, Barnard librarian Vani Natarajan and collaborators brought together Cara Page, Ebony Noelle Golden, and Tiffany Lenoi Jones for a night of reflection on Shange’s works and collective embodied practice of healing justice and ceremony. Last November, when Shange’s revered “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf returned to The Public Theater in New York City for the first time since it premiered in 1976, the audience was filled with Barnard students.

“Ntozake broke through,” Hall said. “She speaks to the soul of colored women and what it means to be a Black woman.”

In February, Barnard’s Movement Lab brought students, faculty, and staff together for “A Woman Who Knows Her Magic” — a multimedia experience of words, sounds, and images from Shange’s works and influences. And from September 8, 2020, to August 16, 2021, the lobby of the Milstein Center for Teaching and Learning will house a new multimedia exhibition, “STUFF,” featuring excerpts from for colored girls and archival materials from Barnard’s Shange archives. “STUFF” can also be experienced through the library’s site.

“STUFF” was spearheaded by Archives & Special Collections director Martha Tenney — who also helped to establish Shange’s archives at the College as well as the Shange Magic Project — and created by artist Dianne Smith and curator Souleo. With butcher paper, fabric, sculptural elements, and video interviews with women sharing their lived experiences with many of the themes found in Shange’s work, the exhibit uses the poem “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff” from for colored girls as inspiration. Watch the video above, featuring Smith and Souleo, who discuss the installation, what it meant to work on an art project inspired by Shange, and more.

“The significance of being here — this is where her archives live, this is where part of her legacy is,” said Souleo. “To be able to tap into that history and to use it as inspiration for this exhibition is really significant. And we’re on the campus where students are learning about her work.”

See a time lapse video below of Smith's installation of “STUFF” at the Milstein Center:

Below, Kim F. Hall, Monica L. Miller, and Martha Tenney share why it’s important to keep Shange’s legacy alive:

What was the inspiration behind “STUFF,” and why install it in Milstein?

Tenney: This exhibit has a prehistory: The beautiful relationship that Kim F. Hall, Monica Miller, and many others at Barnard built with Ntozake Shange ’70 led to a 2013 conference and issue of S&F Online, a course that Kim developed by focusing on Shange’s life and work, and the acquisition of the Shange Papers by the Barnard Archives. In the wake of Ntozake Shange’s passing in late 2018, we held a small memorial service in the Archives reading room, but we wanted to do more celebration of her work and reckon with her legacy at Barnard. This led to the creation of the Shange Magic Project and to the installation of “STUFF.”

When we reached out to Souleo about the idea of adapting i found god in myself, his traveling exhibit marking the 40th anniversary of for colored girls..., for the Milstein lobby, he knew exactly what was needed: a shrine for Ntozake, a site for mourning and healing, and a reclaiming of space in the wake of both Ntozake’s passing and the attack on Alexander McNab in the Milstein lobby. He proposed that Dianne would install her work, which departs from the lady in green’s poem in for colored girls and includes Dianne’s own experiences of intimate partner violence. In “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff,” Shange wrote about all the tangible and intangible things that are taken in a racist and sexist society and reclaimed these things: “now why don’t you put me back / & let me hang out in my own / self.” We hope that the exhibit honors Ntozake’s legacy and provides space for healing and reclamation.

Miller: I would also add here that the organicism of Dianne’s piece was and is also important. The Shange Magic Project has been thinking about all of the more “typical” themes and issues that characterize Ntozake’s work — Black feminism, girlhood, resilience, resistance, language, movement, collaboration — but we’ve also been struck by how much of Zake’s work is about other things: food, nature, elemental things. Dianne’s piece is about “stuff,” and I think about it as the stuff of life, Black women’s lives, the totality of the environments in which we live and thrive.

Hall: I love Dianne’s installation reappearing at Barnard because it is a reclaiming of something very fundamental in women’s experience. “Somebody almost walked off wid alla y stuff” is one of the most unforgettable poems in for colored girls. It is a humorous piece that is also a lament for the things — material, psychological, and spiritual — that women too often give up in the pursuit of love and approval. The installation brings together that “stuff,” in this case powerfully and wittily directing us to Zake’s archive — the “stuff” she left with us [through] her research, her letters, her art, her nipple tassels, and awards — to share with young women who are just at the age when they are tempted to lose themselves for others and need Zake’s inspiration and the healing of the feminist archive that Barnard has built around her. “This is a woman’s trip & i need my stuff”: what more powerful statement can we make in the Milstein Center — with its books, media, archives, Movement Lab, Design Center, Digital Humanities Center — where new generations of Barnard women are remaking themselves by making “stuff” in every form imaginable?

How do the archival materials from the Ntozake Shange Papers add additional layers to the exhibit?

Tenney: There is a part of “alla my stuff” that always makes me think about my work as an archivist when I read it: “i want my own things / how i lived them / & give me my memories / how i waz when i waz there.” Everyone can think of a time when their life was narrated by someone else, their memories represented in a way that they didn’t agree with. I think this is particularly true for people who are not the protagonists in most history books: Black people, Indigenous people, disabled people, queer people. In choosing to place her papers at Barnard, and in choosing to include the intimate records of her life, Ntozake took control of her creative and personal narrative. She also gave an incredibly generous gift to generations of Barnard students who can see themselves in the archives because of her, and to scholars, artists, and so many others who witness her life through her papers. I think it’s only fitting that Souleo has curated materials from the Shange Papers that show her creative process of writing for colored girls… as well as place the choreopoem in a historical context; it was and continues to be a groundbreaking work.

Miller: That was perfect, Martha. As a literature nerd, addicted to language, it is hard to say how much it means, in this very digital age, to sit down with the material work of a writer, the actual words on a page, or any of her ephemera, some part of her thinking, such as the throwaway line or phrase on a postcard that could have been inspiration. I think we all remember that Zake wrote longhand, on yellow legal pads! Ntozake’s papers in this exhibit reflect some of the materiality of the piece itself, as her work and Dianne’s were grown and built from and on paper.

What makes this installation so necessary now?

Miller: In the wake of the police [killing] of Breonna Taylor and ongoing national Black Lives Matter uprisings, Zake’s work, in particular for colored girls, is a major work of witnessing — Black girls know through Zake’s words that they are seen and heard, that their lives, their trauma, healing, and joy, matter. for colored girls importantly explores racial trauma and violence against Black women in a way that is intimate and also generalizable; Breonna was a “colored girl,” and a lot of colored girls have, tragically and criminally, met the same fate as Breonna.

Hall: In an op-ed for Hyperallergic last year, I wrote that “if you are surprised or stunned by recent revelations concerning sexual assault and harassment, it is because you have been, like most of American culture, ignoring Black women. … Having taught for colored girls fairly continuously for the past two decades, it is clear that its impact then and its enduring relevance now are due to the space it gave Black women to name the most hidden, yet ubiquitous aspects of our experiences.”

I continued by saying that “for colored girls is so much more than a litany of Black women’s suffering. It is an insistence that public naming and seeing ourselves in each other can lead to collective purpose. It reminds that [those] traumas, once named, need redress and healing. That we need art — and the spaces to create and enjoy art together — when the pain is enuf.”

Zake’s work also shows us that this redress and healing needs to happen at both an individual and societal level. The colored girls find “god” in themselves and “love her fiercely,” but in holding each other, they also, often, demand recognition beyond themselves and accountability. Zake’s for colored girls did this for Dianne Smith, and we are hoping that Dianne’s work, as it occupies the Milstein Center, will do this for others as well.

Installation crew credit: Barnard’s Library staff members Miriam Neptune, Meredith Wisner, Vanessa Thill, and Martha Tenney were part of the exhibit crew.

For more on for colored girls and videos featured in the exhibit:

- Video: Barnard at the Public Theatre: for colored girls

- “STUFF” videos: “Our Stories;” “Alla My Stuff;” "It Happened to ME"

Dance We Do

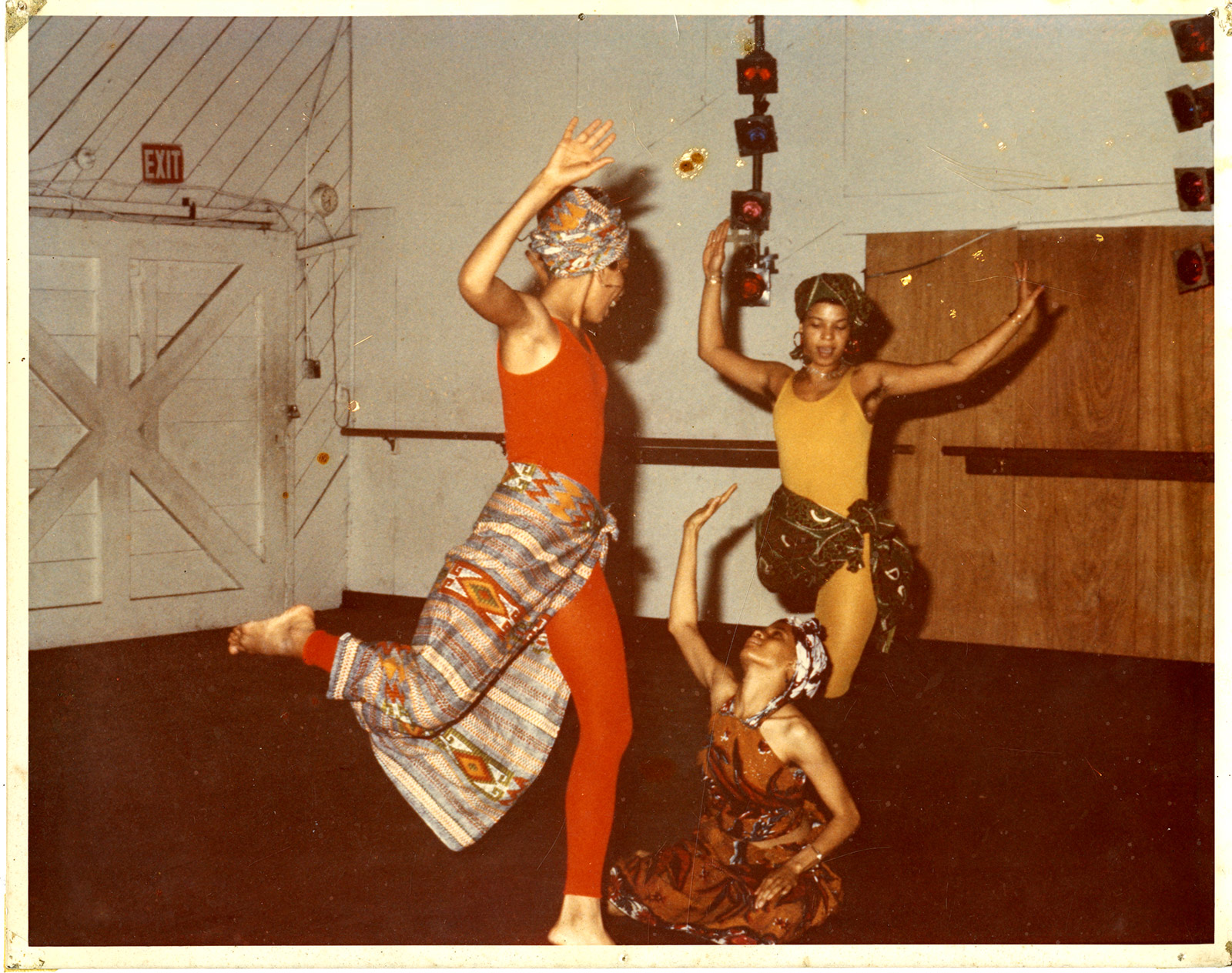

In addition to “STUFF,” Barnard’s Shange Magic Project is partnering with the Department of Dance and Beacon Press to present a virtual celebration of Shange’s first posthumous book, Dance We Do (2020). The book features interviews with Black choreographers with whom Shange danced, studied, and celebrated and serves as a testament to the power of dance and the community it creates.

The launch celebration — which will take place on October 18, Shange’s birthday — will include an introduction sharing how the text was created, prerecorded footage of dance performances, and a panel discussion with dance scholars and practitioners, including several choreographers featured in the book.

“In many ways, Ntozake was ahead of her time, seen in the timelessness of her for colored girls and this book. Dance We Do talks about the world she loved best: the world of Black dance,” said Gabri Christa, an associate professor of professional practice in the Department of Dance who will lead the panel discussion. “Shange would have been delighted to see the dance world taking on [this] dance.”

Martha Tenney echoed Christa’s excitement. “The last time that I saw Ntozake, in September 2018 at Barnard, she shared part of the text that would become Dance We Do,” said Tenney. “It was thrilling to hear her talk about the dancers and choreographers she’s worked with [...] and the way that dance became entangled with her writing practice. [...] It’s so exciting to honor this amazing gift that Ntozake has given dancers and scholars, her love letter to Black dance and to the freedom of bodies in motion.”

Register now to join the celebration.